Taming the Ralph: How to Run AI Coding Agents in a Loop

Learn how to safely run Claude Code in an infinite loop without destroying your codebase. Practical guardrails, git worktrees, and prompt engineering for autonomous AI coding.

If you’ve been following the AI coding discourse, you’ve probably heard about the “Ralph Wiggum Technique” - running a coding agent in an infinite bash loop and letting it ship code while you sleep.

while :; do cat PROMPT.md | claude -p --dangerously-skip-permissions; doneThe results sound magical: teams shipping 6 repos overnight, $50k contracts delivered for $300 in API costs, entire libraries ported between frameworks autonomously.

But here’s what the hype doesn’t tell you: Ralph will absolutely destroy a mature codebase if you let him loose without guardrails.

I learned this the hard way.

The problem with naive Ralph

My first attempt at running Ralph on a production Angular application went like this:

- Asked it to “improve performance”

- Came back to find it had “helpfully” refactored all the imports

- The entire codebase was broken

- Three hours of git archaeology to recover

The issue isn’t that Ralph is stupid. It’s that Ralph is eager. Give Ralph a vague instruction and he’ll interpret it as broadly as possible. “Improve performance” becomes “reorganise the entire architecture while I’m here.”

The key insight: constraint is freedom

The teams having success with Ralph aren’t just running a loop. They’re running a loop with obsessively specific prompts that constrain Ralph to tiny, safe changes.

Here’s what I learned works:

One task per loop, maximum

Not “improve performance across the app.” Not even “improve performance in this module.”

Instead: “Find ONE component without a trackBy function. Add trackBy to that ONE component. Commit. Exit.”

Ralph works best when each iteration is 1-2 story points at most. The loop handles the volume - you handle the scope.

Explicit “do NOT” lists

Ralph responds well to negative constraints. My prompts now include sections like:

### Absolutely Do NOT

- Refactor imports or barrel files

- Rename or move files

- Touch unrelated components "while you're there"

- Make changes you cannot explain the impact of

- Do "improvements" that weren't specifically requestedEvery time Ralph went off the rails, I added another line to this list. Think of it as training a very enthusiastic junior developer who needs explicit boundaries.

Require understanding before action

For complex changes (like migrating to OnPush change detection in Angular), I require Ralph to document his analysis before making changes:

### Before Changing Anything

1. State which component you're targeting

2. Explain what the component does

3. Map out its data flow

4. Explain why your change is safe

5. Only then, make the changeIf Ralph can’t articulate why a change is safe, he shouldn’t make it. This catches most of the “seemed like a good idea” disasters.

Bottom-up, not top-down

For architectural changes, order matters. When migrating change detection strategies, you must start with leaf components (no children) and work upward. A parent can’t safely change until its children are ready.

My prompt explicitly encodes this:

### Priority Order

1. Shared presentational components (no children)

2. List item components (*-card, *-item, *-row)

3. Feature components (only after children migrated)

4. Page/container components (LAST)Red flags that trigger “skip and move on”

Some components are too complex for autonomous changes. My prompt includes:

### Red Flags - Pick a Different Component If You See

- Already using detectChanges() (someone handled this manually)

- Injects NgZone (complex zone management)

- Uses framework lifecycle hooks that fetch data

- Has plugin/native code dependencies

- You're unsure about any patternThis prevents Ralph from touching the hairy parts of the codebase that need human judgement.

The safety net: git worktrees

Never let Ralph work on your main branch. Use git worktrees to give Ralph his own isolated sandbox:

# Create a branch for Ralph

git branch ralph-experiments

# Create a worktree (separate working directory, shared history)

git worktree add ../project-ralph ralph-experiments

# Now Ralph works here, your main work is untouched

cd ../project-ralph

while :; do cat PROMPT.md | claude -p --dangerously-skip-permissions; doneBenefits:

- Your VS Code windows and main branch stay clean

- You review Ralph’s commits before merging

- Easy to nuke and restart if things go wrong

git worktree remove ../project-ralphand it’s gone

Adding build verification

Don’t just let Ralph commit blindly. Add verification to the loop:

while :; do

cat PROMPT.md | claude -p --dangerously-skip-permissions

# Verify it still builds

if ! npm run build 2>/dev/null; then

echo "BUILD BROKEN - reverting"

git reset --hard HEAD~1

fi

sleep 5

doneYou can extend this with linting, type checking, or test suites. The faster Ralph gets feedback on broken changes, the less damage accumulates.

Visual regression as the ultimate guard

If you have visual regression testing (comparing screenshots between environments), this is Ralph’s perfect companion. The loop becomes:

- Ralph makes a change

- Visual regression runs automatically

- If screenshots differ unexpectedly, revert

- If screenshots match (or differ as expected), keep the commit

This catches the subtle breaks that pass type checking but break the actual UI.

When NOT to use Ralph

Ralph excels at:

- Repetitive transformations across a codebase

- Porting code between frameworks

- Greenfield projects with clear specs

- Maintenance tasks with well-defined patterns

Ralph struggles with:

- Ambiguous requirements

- Changes requiring architectural judgement

- Security-sensitive code

- Anything where “move fast and break things” isn’t acceptable

The meta-lesson

The Ralph technique isn’t really about running a loop. It’s about prompt engineering for autonomy.

Every failure teaches you something to add to the prompt. Every success validates your constraints. Over time, your prompt becomes a specification so precise that autonomous execution becomes safe.

As Geoff Huntley (who popularised the technique) puts it: “That’s the beauty of Ralph - the technique is deterministically bad in an undeterministic world.”

Ralph will fail in predictable ways. Your job is to predict those ways and encode the guardrails.

Getting started

- Pick a low-stakes task (adding trackBy functions, not refactoring auth)

- Write a prompt with explicit constraints and “do not” rules

- Create a worktree so Ralph can’t touch your main branch

- Run single iterations first:

cat PROMPT.md | claude -p --dangerously-skip-permissions - Review every commit until you trust the prompt

- Only then, add the

whileloop

Start small. Build trust. Add scope gradually.

Ralph is a powerful technique - but only after you’ve trained him not to eat the furniture.

Enjoyed this article?

Get notified about new posts and product updates.

Related Posts

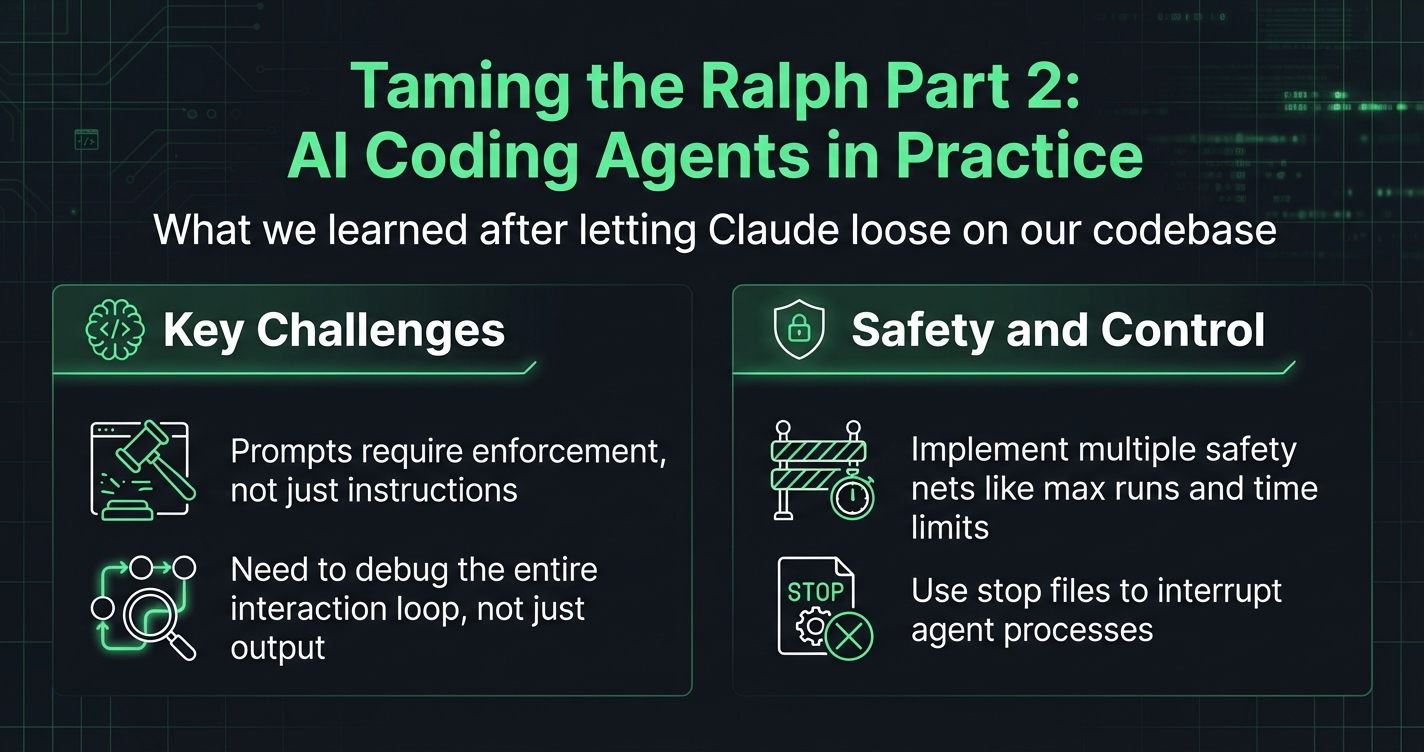

Taming the Ralph Part 2: AI Coding Agents in Practice

What we actually learned after letting Claude loose on our codebase for a day. Loop safety controls, prompt engineering patterns that work, and bridging automated and manual testing.

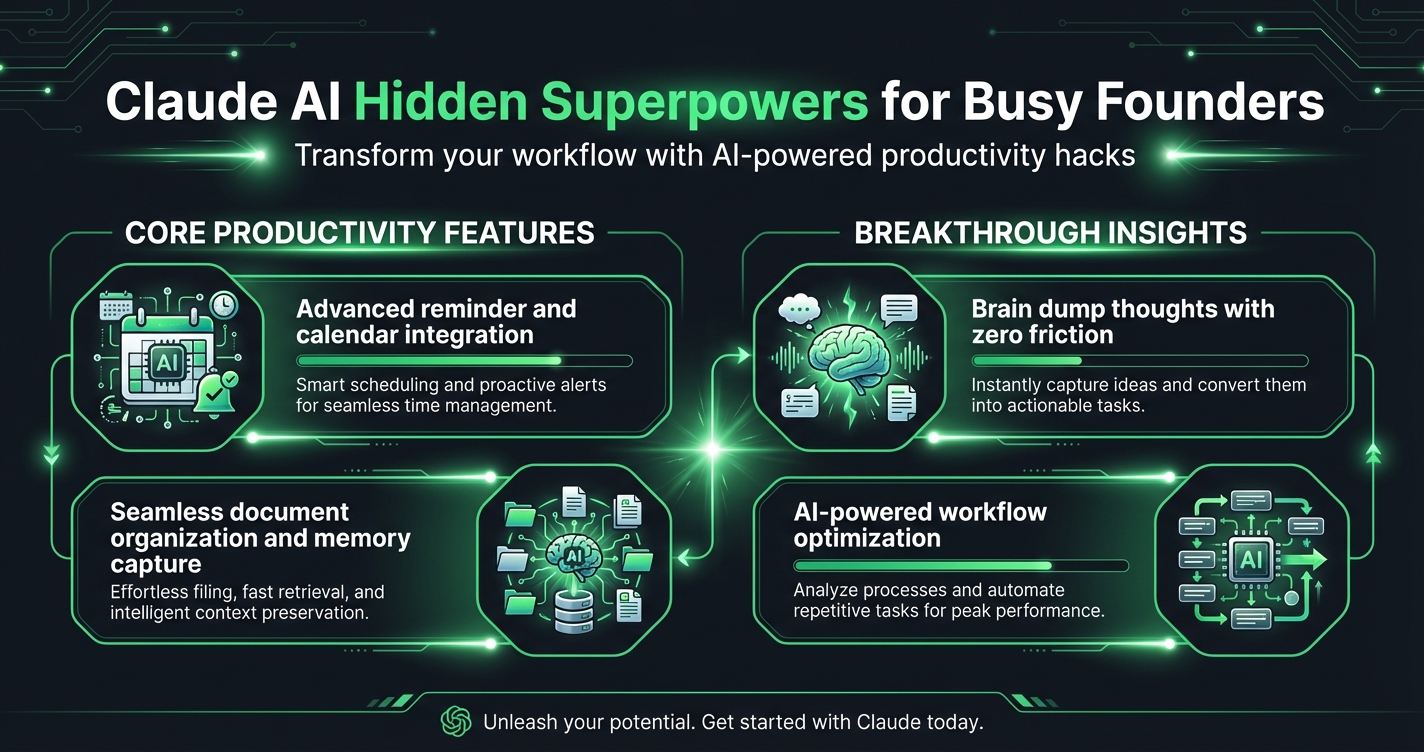

Claude's Hidden Superpowers for Busy Founders

Reminders, calendar, memory, document creation - I just discovered Claude can do all this. Here's everything I didn't know after months of use.

Taming the Ralph Part 3: In Practice

After running an AI coding agent overnight, here are the actual performance numbers. 81% improvement in layout shift, 65% fewer long tasks, and what metrics actually matter.